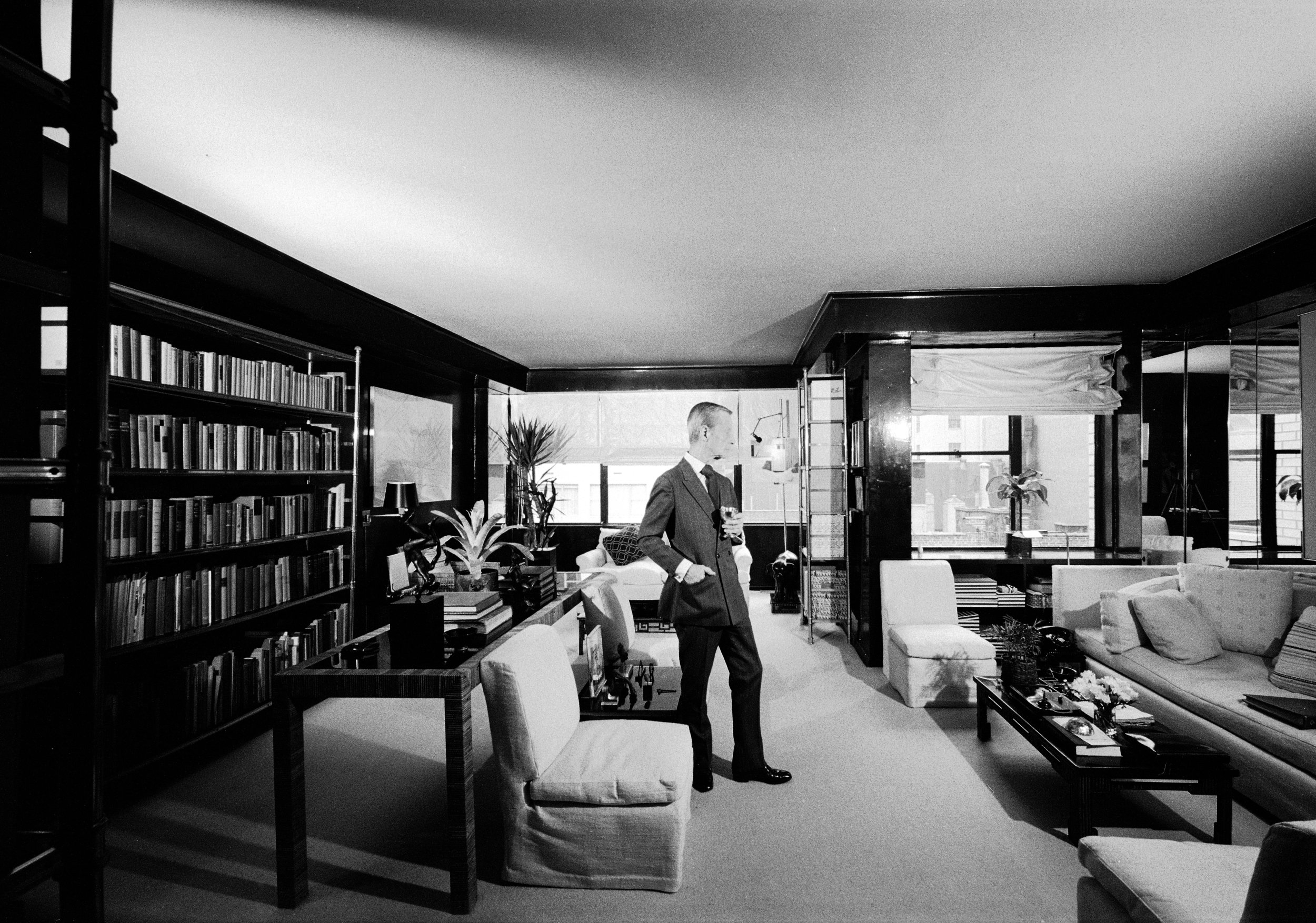

Interior decorator Billy Baldwin in his self designed apartment, circa 1974

(Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

Most design aficionados have "Design Heroes"- designers they look to for inspiration. The same holds true for interior design professionals, who regularly seek to reinterpret great design from the past for their own clients. In our office, we all keep a cache of design books behind our desks for reference. Without question, the ones with the most dog-eared pages are about Billy Baldwin, who actually disliked the term designer and preferred to be called a decorator.

William Williar Baldwin, Jr. was born May 30, 1903 and grew up in a fashionable neighborhood in Baltimore, Maryland. His father owned a reasonably successful insurance agency and his mother hailed from one of the wealthiest families in Maryland, with roots back to colonial Connecticut.

When Billy was ten years of age, he encountered the work of Henri Matisse for the first time in the Baltimore home of Etta and Dr. Claribel Cone, the influential art-collecting sisters and friends of Gertrude Stein. He credited Matisse “for emancipating us from Victorian color prejudices” and advocated for his palette of bright, bold hues. Later in life, he would credit that childhood visit for first instilling in him a love of interior design.

Twice a year, William Baldwin, Sr.- a handsome man with a reputation for being fastidious about his grooming and attire- would take young Billy to the see the Saville Row tailors visiting Baltimore from London. The two would be outfitted with custom suits, jackets, and shoes. Billy would come to share his father’s love of clothing and later in life would be named to the International Best-Dressed List Hall of Fame.

Billy attended the Gilman School for Boys in Baltimore, except for one year when he was fifteen. His father, who was worried about his son spending too much time with his mother, sent his son away that year to the Westminster School for Boys in Simsbury, Connecticut. Billy went on to attend Princeton for a short time until he was asked not to return due to poor grades.

Back in Baltimore, Billy briefly worked at his father's insurance company and then at a local newspaper. At this point, his mother asked her longtime interior decorator, C. J. Benson, to do her a favor and employ her son. It was under C. J. Benson's tutelage that Billy learned about the decorating business, including how to effectively work with drapery and upholstery workrooms, manage installations, and how to attract and retain clients.

In 1930, Ruby Ross Wood, one of New York’s grand dame decorators, visited a stylish house that Baldwin had created. She promptly wrote to him declaring it “a beacon of light in the boredom of the houses around it,” and invited him to come to the city to assist in her business as soon as the economy improved. He arrived five years later and worked for her until she died in 1950, absorbing all of her decorating wisdom, which he later distilled down to “’the importance of the personal, of the comfortable, and of the new.” After her death, he stayed with the firm for two years to assist in finishing any outstanding commissions and to wind down operations.

In 1952, Billy and his assistant at Ruby Ross Wood, Edward Martin, opened Baldwin Interiors. The name of the firm was changed in 1955 to Baldwin & Martin, Inc. One of the firm's first clients was renowned dress designer Mollie Parnis. After the project was published in Vogue, business began to boom. By the 1960s, just about every American taste-making blue blood was his client, including the Nan Kempner, the Paul Mellons, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Diana Vreeland, the William S. Paleys, Kenneth's hair salon and the Round Hill Club in Greenwich .

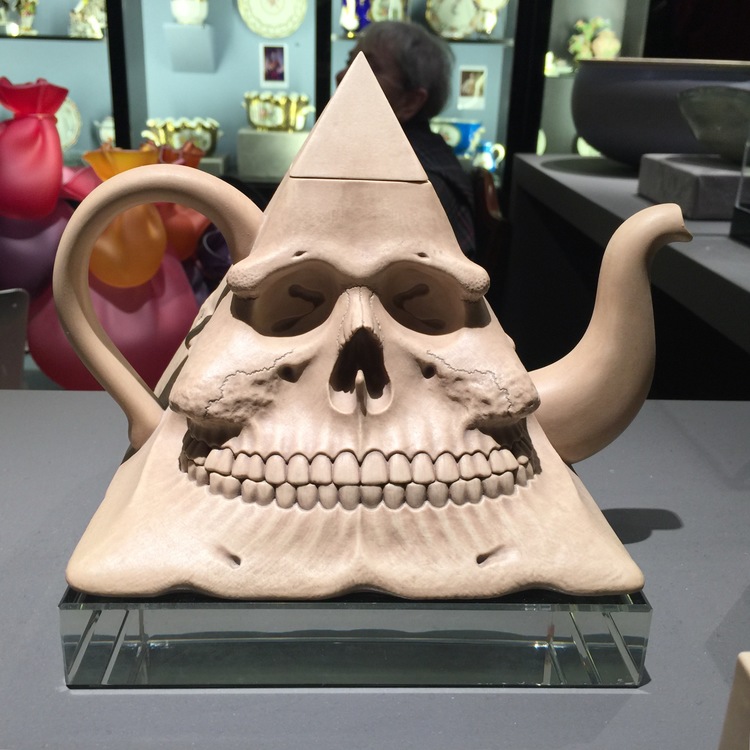

Cole Porter's Waldorf Towers apartment, with its floor to ceiling Directoire-inspired tubular brass bookcases placed against lacquered tortoiseshell-vinyl walls.

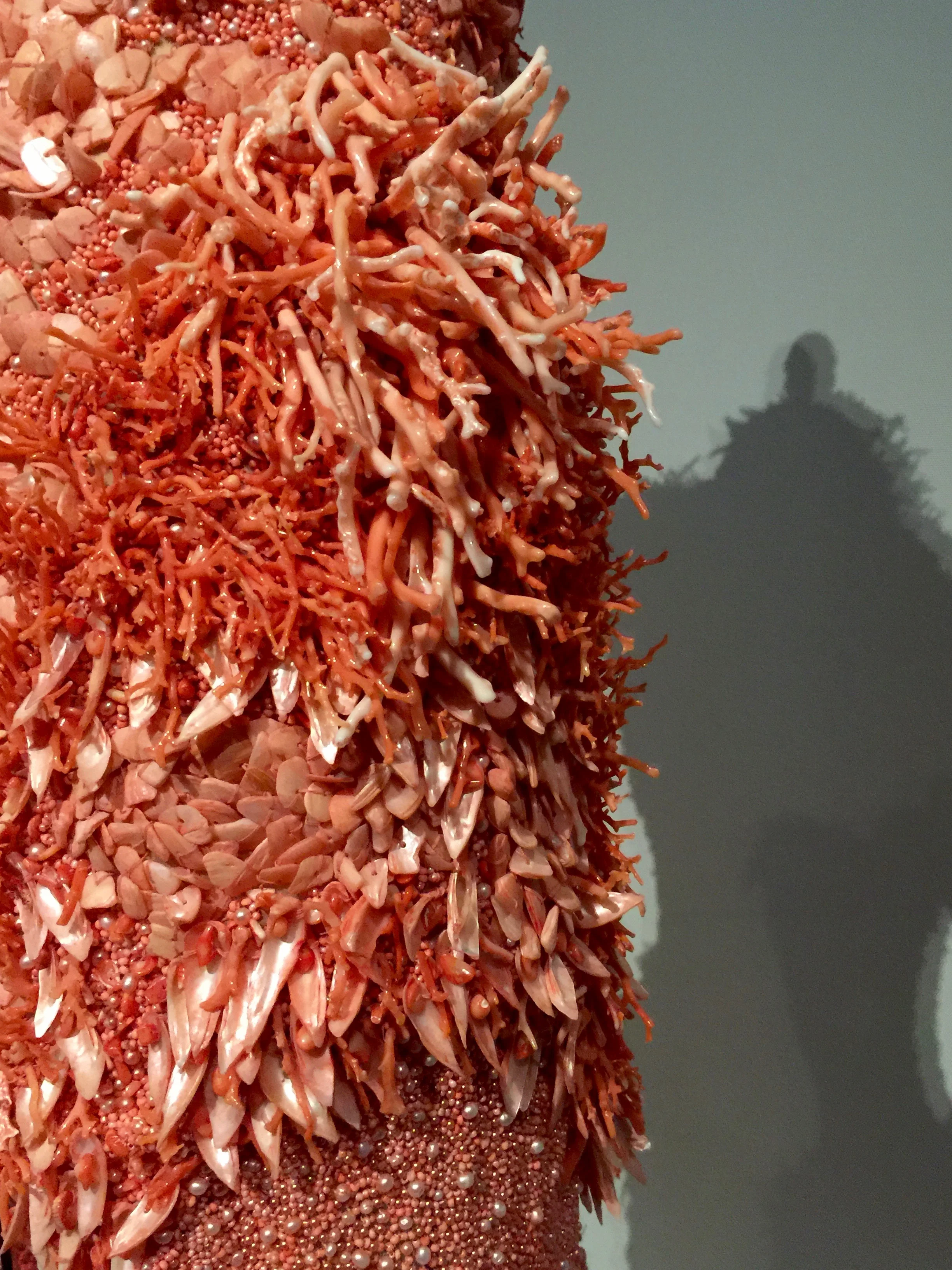

Diana Vreeland requested that Baldwin transform her drawing room into a “garden in hell.”

The Baldwin-designed Manhattan home of Mr. and Mrs. Lee Eastman.

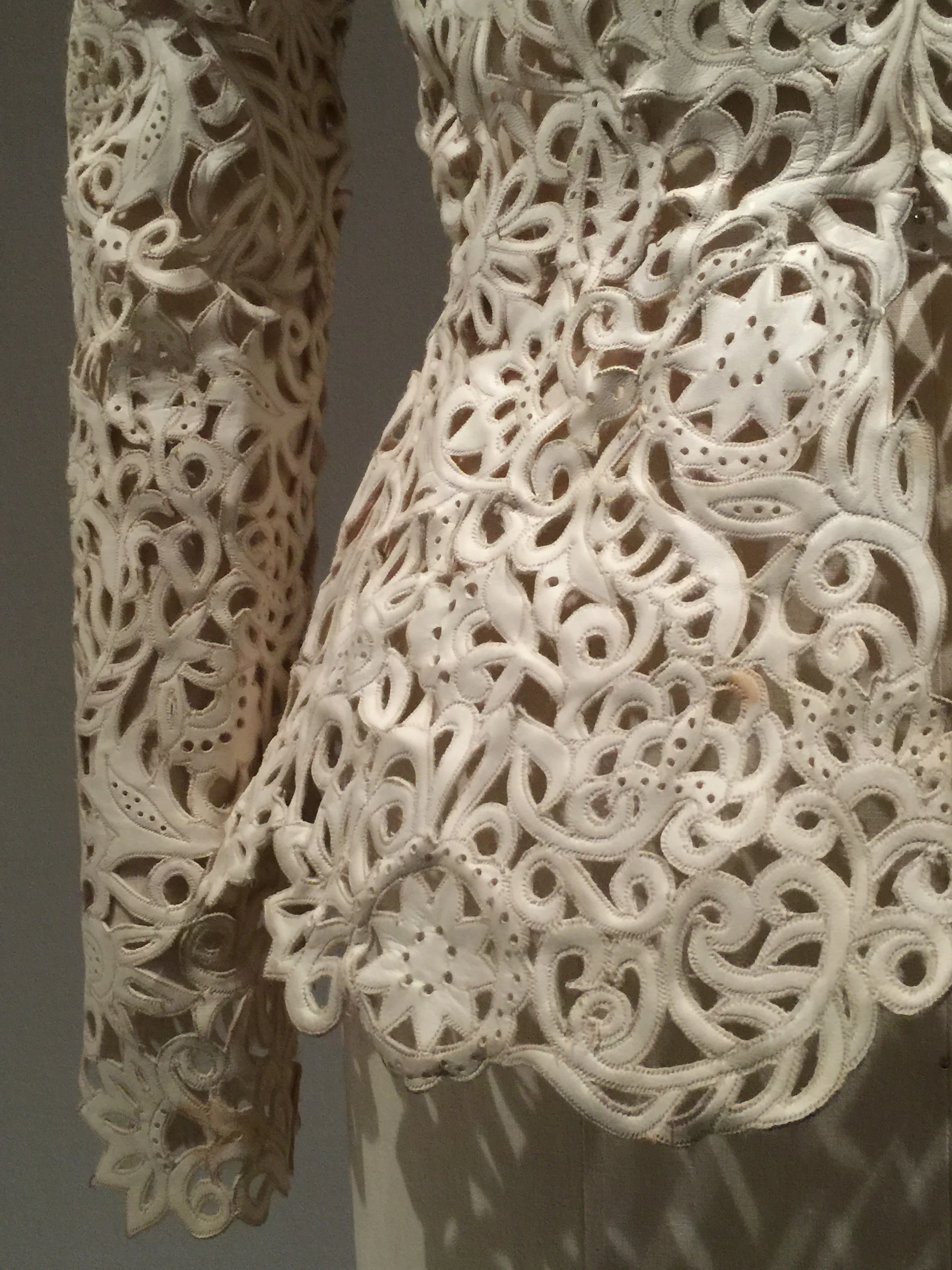

Baldwin’s style was both classic and modern. He generally disdained the ornate in favor of pared-down, cleaner look which was recognized as distinctly American. Hallmarks of a Baldwin project include cotton- he called it “his life" but he also like blue denim, white plaster lamps, pattern on pattern, dark walls, matchstick blinds, swing-arm brass lamps, armless slipper chairs, corner banquettes, wicker-wrapped Parsons tables, and lots of books. His pet aversions were satin and damask, ostentation of any kind, clutter, fake fireplaces and false books.

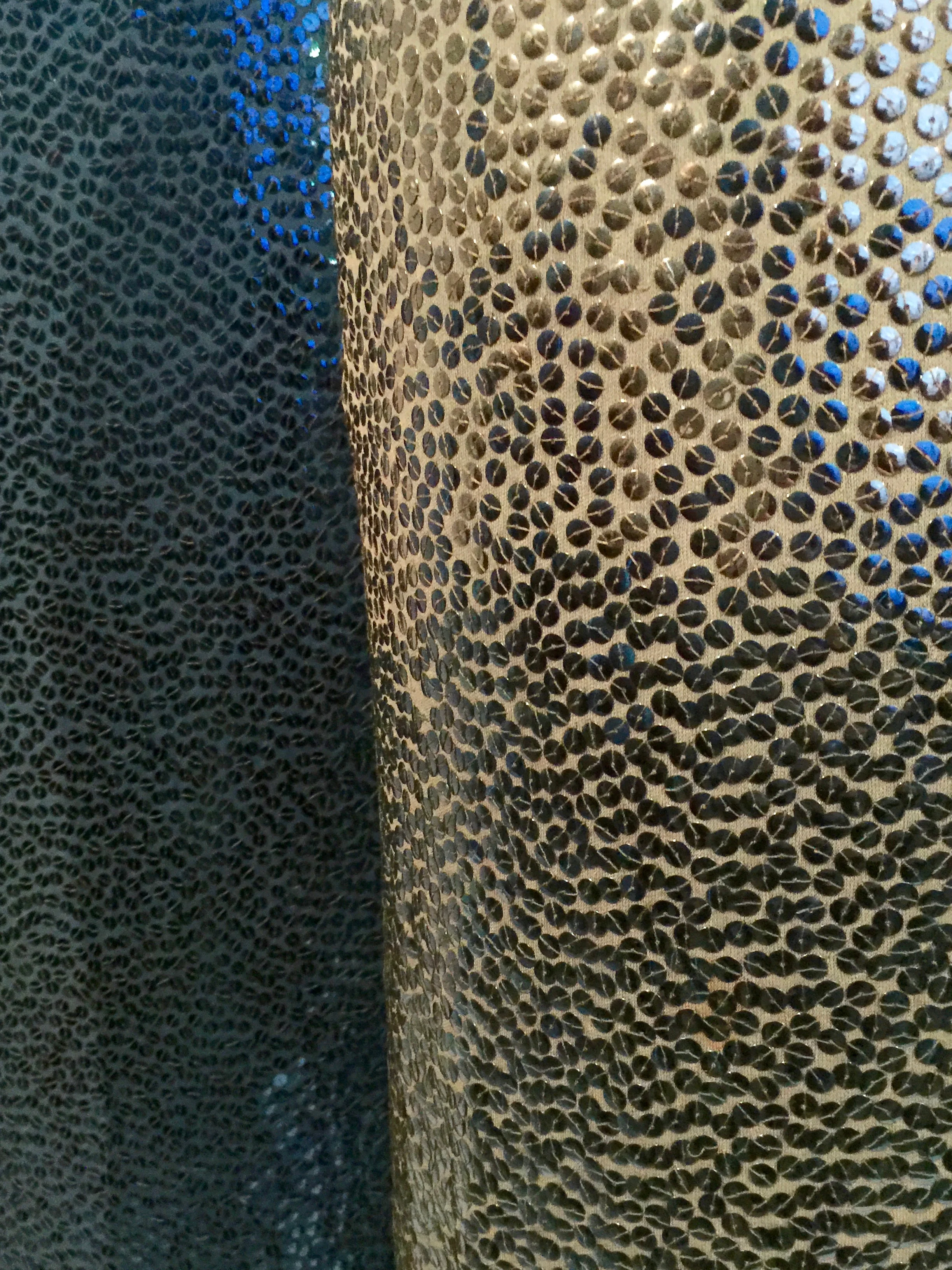

Billy Baldwin designed this patterned black-and-white textile, Arbre de Matisse Reverse (formerly called "Foliage"), in 1965 with and for client Woodson Taulbee. The inspiration came from the black ink tree in the background of the Matisse painting above the sofa.

Baldwin believed the ultimate luxury was comfort and declared that “first and foremost, furniture must be comfortable". His taste in furniture was eclectic and he generally tried to use some of the furniture that the client already owned. He insisted, however, on a common thread and that thread was quality. To that end, he routinely favored contemporary pieces over reproductions. He would, when inspired by need or nature, design his own pieces such as the iconic Directoire-inspired brass etagere created for Cole Porter, the cane wrapped chair adapted from a Jean-Michel Frank design and handcrafted by Bielecky Brothers, Inc., the "X" bench, and the Baldwin slipper chair. The slipper chair has an interesting back story. Adapted from a mini-Lawson sofa without arms designed by Ruby Ross Wood, Baldwin further shrunk the shape into what has become his iconic armless chair- perfect for perching at a cocktail party or watching television.

In the early 1960's Billy Baldwin suffered a tremendously embarrassing personal setback. Due to errors on his personal accounting, he was indicted on federal income tax evasion. To keep him out of prison, a client/friend paid his fines. The government garnished income for the rest of his life and he was forced to sell his home and move into a studio on East Sixty-first Street. The irony is that this studio would become his most photographed project.

Baldwin made his assistant, Arthur Smith, a partner in the firm in 1971 and the name was changed to Baldwin, Martin & Smith. Just over two years later at seventy years of age, Billy decided to retire and the company was sold to Arthur Smith who promptly renamed it Arthur E. Smith, Inc.

Baldwin continued to live in Manhattan for four years after his retirement but finally concluded that it was too expensive to remain there if he was not working. At that point, he decided to move to Nantucket, where he had first summered with his mother as a boy and visited regularly throughout his life. This decision presented another set of problems, however, as the island did not have many year round rentals and he did not have the funds to purchase a home. Two friends, Way Bandy and Michael Gardine, came to his rescue and converted a small structure behind their own home into a suitable two-room guest house for Baldwin. Billy claimed that he liked it better than any place he had lived since growing up in his family home in Baltimore.

When Baldwin moved to Nantucket, he was suffering from advanced emphysema. The cold, damp winters on Nantucket only made it worse. Although he was able to escape to warmer climates for the first few years, his condition declined and, on November 25, 1983, Billy Baldwin passed away. Prior to his death, he had requested that there be no memorial services. His ashes were scattered on a Nantucket beach.

Billy Baldwin left a design legacy that is visible in photographs of his designs, the furniture he created, and also through a series of lectures he gave in 1974 at the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum in New York City. The following quotes are as relevant and useful today as when he first delivered them:

"There must be sympathy, congeniality, and mutual admiration between you, your architect, and your decorator. There is a lot of hard work ahead, and it must be done with joy and smiles, not scowls."

"Many architects build from the outside in, instead of from the inside out. What good is beautiful fenestration if it creates unworkable wall spaces?"

"The first step in decorating and furnishing a room or a house is having an up-to-date floor plan."

"Briefly, I want us to think about photographs. I personally like to see them on table in any room but I prefer two see a lot of them grouped on a tabletop in small rooms."

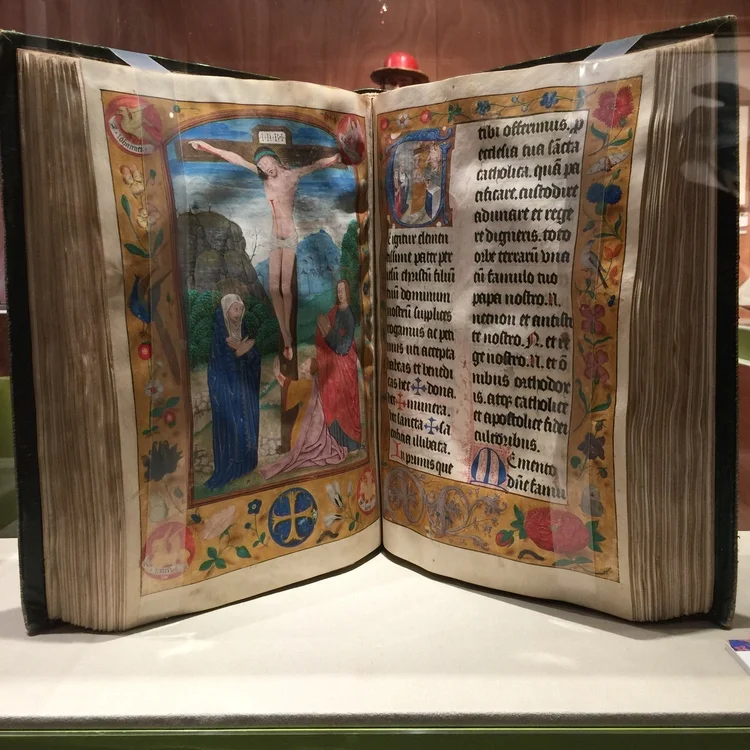

"I have always contended that books are the best decoration of all. Certainly there is not a room in the house where they do not fit. I will confess that I cannot see them in a room that is used only for eating. It is very difficult to eat and read."

"Trends is a word I hate. The inventions of manufacturers, trends are used to promote business. Trends are the death knell of the personal stamp in decorating. If I found that something that I was doing had become a trend, I would run from it like the plague."

"In the end, decorating is all about color. Think about colored flowers on bright white cotton and, in the same room, right next to this celebration of color, is more color- fresh flowers, lots of them.”

Baldwin’s own New York City apartment.

To learn more about Billy Baldwin:

"Billy Baldwin, The Great American Decorator", by Adam Lewis

"Billy Baldwin Decorates", by Billy Baldwin

"Billy Baldwin Remembers", by Billy Baldwin

"Billy Baldwin, an Autobiography", by Michael Gardine